What Nvidia's Rubin CPX tells us about data centres of the future

The future isn't 600kW racks everywhere - it's multiple power tiers under one roof.

Data centres hog headlines a lot these days. And no wonder, given their impact on resource usage, the jaw-dropping capital outlay of AI data centres, and how AI is changing everything as we know it.

But developments within data centres aren't as cut and dried as they appear from the outside. As I observed during my fireside chat with Oracle's Dan Madrigal in July, the sheer rate of change means that even those building cutting-edge data centres have to make educated guesses and green-light unproven systems fresh from the factories.

With today's data centres already struggling to keep pace with change, what will tomorrow's facilities need to handle? This week's announcement of Nvidia’s Rubin CPX might offer some clues about where data centres are headed.

The Rubin CPX and the inference play

Modern data centres are heavily influenced by the infrastructure needed for the latest AI models. From Hopper GPUs requiring up to 50kW per rack, to Blackwell GPUs at 130kW, and even the proposed Rubin Ultra GPUs at 600kW per rack, data centre design has evolved at breakneck speed over the last three years.

Yet AI inference hasn't received much attention. Yes, we know AI inference will overtake AI training at some point – every chart I've seen over the last two years shows this trajectory. Sure, companies like Groq have launched specialised inferencing chips at 20kW per rack and are making steady inroads in the enterprise. But the focus has never been on inferencing.

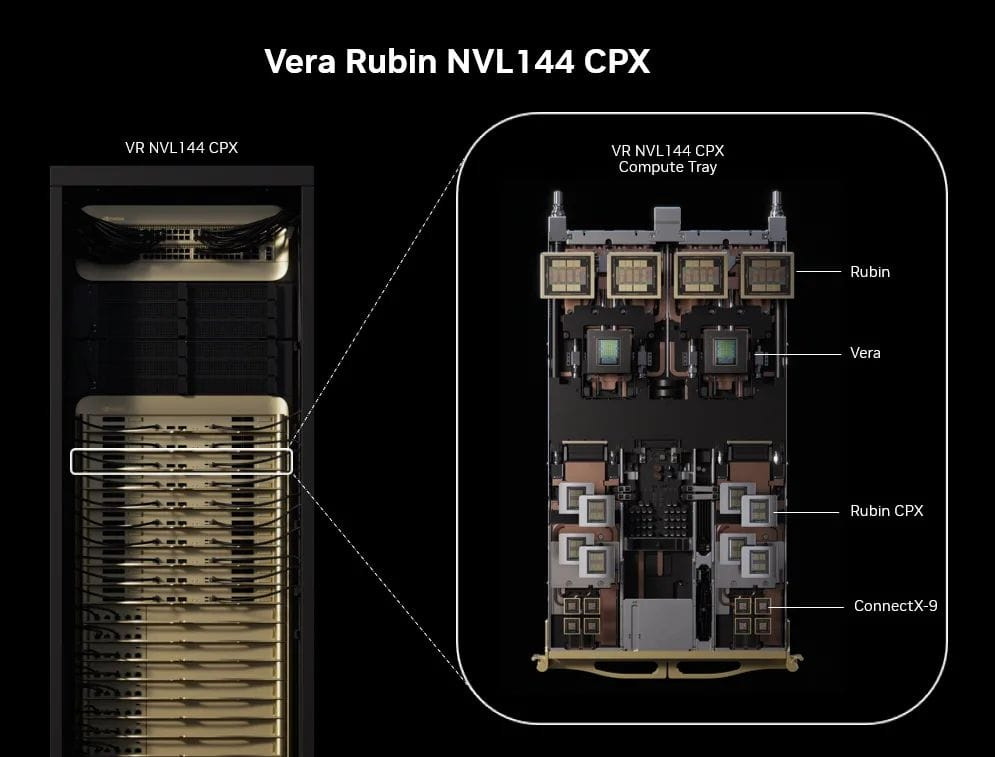

This changed this week when Nvidia unveiled its upcoming Rubin CPX chip, scheduled to ship by end-2026. The CPX represents a completely new class of GPU designed specifically for post-training workloads. And it does this in a way that leverages Nvidia's strengths while achieving further lock-in to its already tightly coupled ecosystem.

What's clever here is Nvidia's new disaggregated inference architecture. The Rubin CPX handles the prefill and context phases of generative AI, reducing the load on more expensive, full-fledged GPUs which can then focus on the actual generation phase.

It also aims to reduce costs. The chip uses much cheaper GDDR7 RAM, albeit in higher quantities, features a monolithic die to lower manufacturing costs, and maintains the 130kW-rack energy footprint of existing Blackwell GPUs, making deployment possible in racks designed for Blackwell.

One could argue that Nvidia is moving decisively to capture a growing market before competitors entrench themselves. I believe that's true, but as I thought about it, I realised there's more to it. But more on that later.

Not everyone needs an AI data centre

I've previously written that data centres are diverging into AI data centres and enterprise data centres, and that this split is accelerating. We're witnessing the emergence of two fundamentally different types of data centre, each with radically different power, cooling, and infrastructure requirements.

Since last year, I've made a concerted effort to enquire about rack densities. I've asked CEOs with new data centres, country leaders overseeing multiple facilities, and vendors selling GPU servers. Despite expecting high double-digit or even triple-digit kW deployments, it turns out high-density racks are still a rarity.

One country leader told me about low take-up for optional liquid cooling systems capable of handling up to 40kW at an existing facility. The reason? Customers simply don't need it. This paints quite a different picture from the one promoted by certain vendors with liquid cooling systems to sell.

To be clear, I'm not saying high-density workloads aren't required; the reality is just more nuanced for data centres not used by tech giants for AI training. Just across the causeway, many data centre operators have liquid cooling and high-density deployments. But look closer and you'll notice most have allocated substantial capacity for non-liquid cooled workloads.

What the Rubin CPX shows us is that even within AI data centres, workloads will be segmented into multiple power tiers. Put another way, 600kW racks are probably further off than we think, or will only be deployed in even smaller sections of data centres than today's Blackwell GPUs occupy.

Welcome to the multi-density data centre

This reality isn't lost on Nvidia. Here's what I think: Nvidia isn't confident the data centre industry will be ready for Rubin Ultra GPUs with their 600kW rack requirements by 2027. Beyond capturing a slice of the inference market, Nvidia is setting the stage for data centres with multiple power tiers.

This makes sense when you consider what needs to change for 600kW racks. Dedicated transformers for every pair of racks. Complete elimination of air cooling. Redesigned structural support. Switching from copper bus bars to alternative materials. The list goes on.

Most data centres haven't even reached 50kW racks, and cutting-edge deployments are just getting comfortable with 130kW. Expecting another radical transformation within three years seems optimistic at best. The Rubin CPX allows operators to standardise on 130kW racks whilst accommodating spot deployments of 600kW racks where absolutely necessary.

At worst, users could simply space out their GPUs across more racks. Remember Meta’s recently unveiled "Catalina" Open Compute rack with two NVL36 racks supported by four racks of air-to-liquid CDUs - Meta calls them air-assisted liquid cooling (AALC) sidecars? That's pragmatism to me.

What will the data centre of the future look like? Not the monolithic, one-size-fits-all facility we've known. I think we're heading toward mixed-density environments where different workloads occupy purpose-built zones.

In that sense, Nvidia's Rubin CPX is a recognition that the future of AI demands flexibility. It is about building systems that actually work with the infrastructure that we (will) have, in data centres designed to accommodate diverse computational needs without forcing everything into the same infrastructure mould.

And that's probably exactly what Nvidia is counting on.

A version of this first appeared in my free Tech Stories newsletter that went out earlier today. This includes a digest of other stories that I wrote this week. To get it in your inbox, sign up here.

Cooling is likely the real bottleneck. Air → liquid → immersion → maybe cryogenic. As GPT-likes scale and inference workloads run longer, the cooling load only compounds.

It seems like Nvidia plans to keep with direct to chip cooling. Just spoke to a data centre building Nvidia's cloud - the real challenge is the data centre - it must be rebuilt (again) to support 600kW racks.