The problem with AI is human

What if the biggest risk of AI isn't that it replaces us, but that it stops us from growing?

The introduction of AI threatens to upend how we work and learn. In a Substack piece titled “We’re all thinking about AI wrong” last month, I argued that we are all approaching AI from different perspectives. Like the classic blind men and the elephant parable, each person touches a different part of the animal and draws wildly different conclusions.

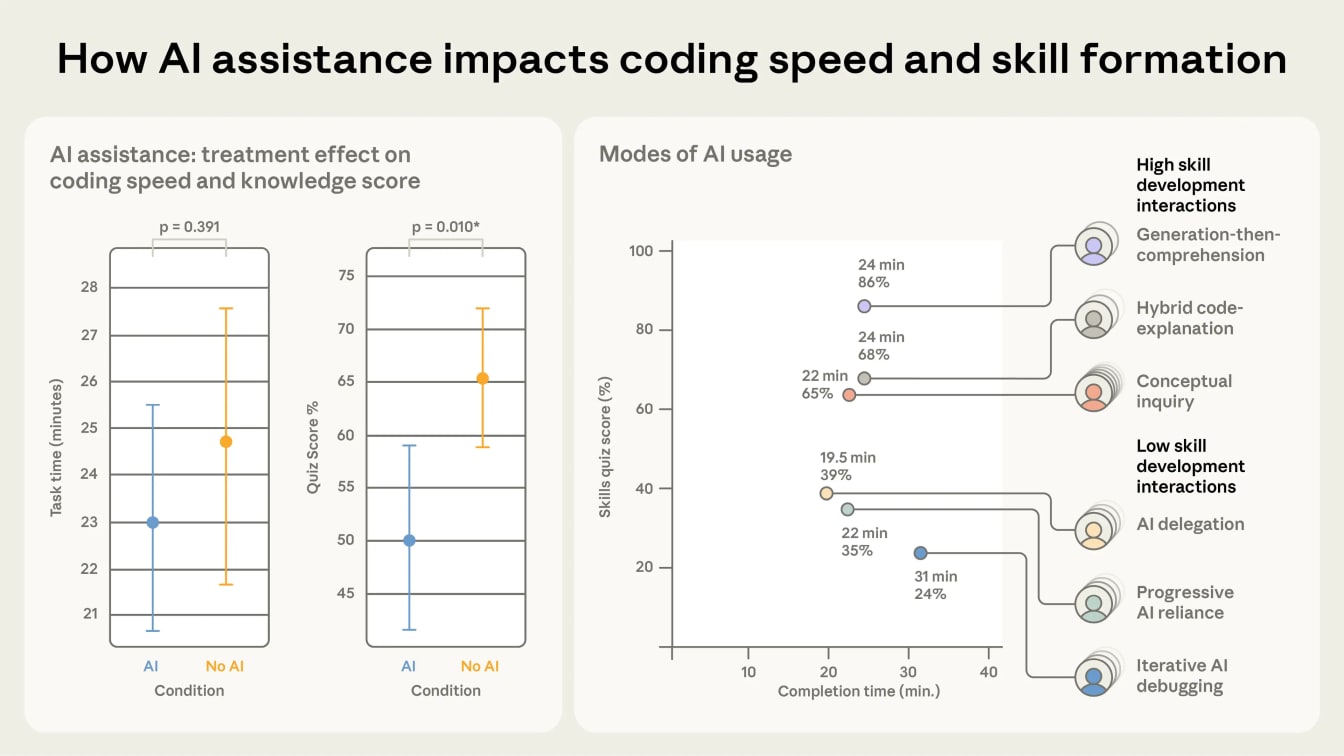

Just last week, a new study published by Anthropic shed new light on the impact of AI on how software engineers work. The researchers manually annotated screen recordings to identify how participants approached their assigned tasks, yielding fresh insights into different ways of using AI and the outcomes in terms of mastering new skills.

I found the report highly relevant beyond coding, particularly in how to optimally apply generative AI in our work. The catch is that using it the “right way” runs against our instinct to take the easy route. In other words, AI doesn’t just change how we work, it tests whether we still want to learn.

The illusion of competence

We already know that AI can help people do their jobs faster. But does this come with trade-offs? Well, new research from Anthropic has confirmed what many of us had long suspected: overreliance on AI can hinder the acquisition of new skills.

A group of 52 software engineers were asked to perform a 30-minute coding assignment in Python, a language they were familiar with. In the study, they were required to write the code for a relatively advanced task using a Python library that was new to them. A 25-minute quiz was administered immediately after to test for mastery of the concepts from the assignment.

Unsurprisingly, those who made use of AI fared significantly worse in the quiz. What’s worth noting is that AI use didn’t automatically mean a lower score - how individuals used AI did. Put simply, those who scored well made the effort to understand the code produced by AI, either by asking for explanations or solving bugs manually.

In short, the higher scorers used AI to speed up their understanding of the unfamiliar library and to code better, not merely to complete the task. They took the extra effort to grapple with the underlying concepts, asynchronous programming in this case, even as they used AI, gaining both productivity and new coding skills.

The concern, as noted by the study’s authors, is the potential for AI to stunt the skill development of junior engineers. They wrote: “[To] accommodate skill development in the presence of AI, we need a more expansive view of the impacts of AI on workers... productivity gains matter, but so does the long-term development of the expertise those gains depend on.”

Writing is thinking

The Anthropic study also underscored my realisation that there are many ways to apply generative AI to writing. Yet even from this sprawl, they can be broadly categorised into two distinct camps: approaches that deepen our expertise, and those that offer little more than one-off productivity boosts.

The danger of leaning too heavily on the latter is that we stay stuck with mediocre skills. And because writing is thinking, AI becomes a crutch that ensures we never learn to stand on our own two feet when it comes to sparking fresh ideas and sharpening our judgement.

When I first tried ChatGPT, I was as fascinated with the idea of learning advanced prompting techniques as everyone else was back then. Remember the tricks? Emulating the style of a favoured author, chain-of-thought prompting, storytelling frameworks?

My problem was I could see the flaws in AI-generated copy as clear as day, regardless of every technique I tried. Moreover, the compulsive overuse of prose techniques by large-language models (LLMs) grated on my taste. Thankfully, this meant I kept writing practically everything manually, though I never stopped experimenting with AI.

What changed was my approach. Rather than trying to get AI to write for me, I shifted towards using it to become a better writer instead. I now write considerably faster than I ever have, while producing pieces with stronger insights. It doesn’t end with writing though. The practice itself sharpened my thinking as I examined issues critically. Often, what I set out to write would morph into something else as the arguments shaped themselves.

The era of synthetic coherence

This wouldn't be possible leaning heavily on AI. Yet the temptation to do exactly that has never been greater. It used to be that being able to put words on a page took effort, which meant any published content broadcast a signal about competence and value. No longer. AI can generate copious coherent-looking text in seconds, complete with beautifully illustrated infographics.

The deeper issue is that AI doesn’t just produce passable text. It excels at something I’d describe as synthetic coherence: the ability to make even erroneous arguments read well. Social media platforms are now inundated with this kind of AI slop: content that looks good at first blush but falls apart on closer inspection by anyone with even a rudimentary knowledge of the subject matter.

This brings us back to the core problem: the human tendency to choose the path of least resistance. This flood of mediocre content isn’t a technology problem. It is what you get when thousands of people choose the shortcut rather than the struggle of thinking.

The internet democratised the sharing of knowledge, allowing thinkers and experts to easily share their opinions and works. AI, on the other hand, is rebuilding the wall the internet tore down, allowing anyone to swamp online spaces with an unending firehose of content, burying everything under a layer of mediocrity.

But where does it leave writers? With a choice to make.

For those who see writing as self-actualisation, it remains one of the most powerful tools: the act of putting thoughts into words forces a rigour that no amount of AI prompting can replicate. We write not just to be read, but to become sharper versions of ourselves.

The problem with AI is human. And the only way to solve it lies within each of us.

A version of this first appeared in the commentary of my free Tech Stories newsletter that goes out every Sunday. This newsletter comes with a digest of other stories that I wrote in the preceding week. To get it in your inbox, sign up here.